Last week was Nanakusa no Sekku, the festival of the seven herbs in Japan, that marks the end of Oshugatsu, the Japanese New Year. On this day – typically in the morning Japanese – people eat Nanakusa Gayu. This is a variation of rice porridge called okayu that is typically served to sick people, because it is soft and rather bland. With my youngest daughter being less than a year old and an addict to Japanese food, I found myself making okayu quite often in the past months and I must admit that it ranks rather low in my Japanese culinary repertoire.

Nevertheless Nanakusa Gayu is traditionally eaten on the seventh day of the new year as a simple soup made with rice and water (proportion 1:3), or a light dashi broth and seven different kinds of herbs (each having a unique health promoting property) that are quickly blanched and then finely chopped to be added at the end. The soup is meant to let the “overworked” stomach and digestive system rest and bring longevity and health in the coming year.

The traditional seven herbs that are added to the dish are:

– seri — Water Dropwort

– nazuna — Shepherd’s Purse

– gogyō — Cudweed

– hakobera — Chickweed

– hotokenoza — Nipplewort

– suzuna — Turnip

– suzushiro — Daikon

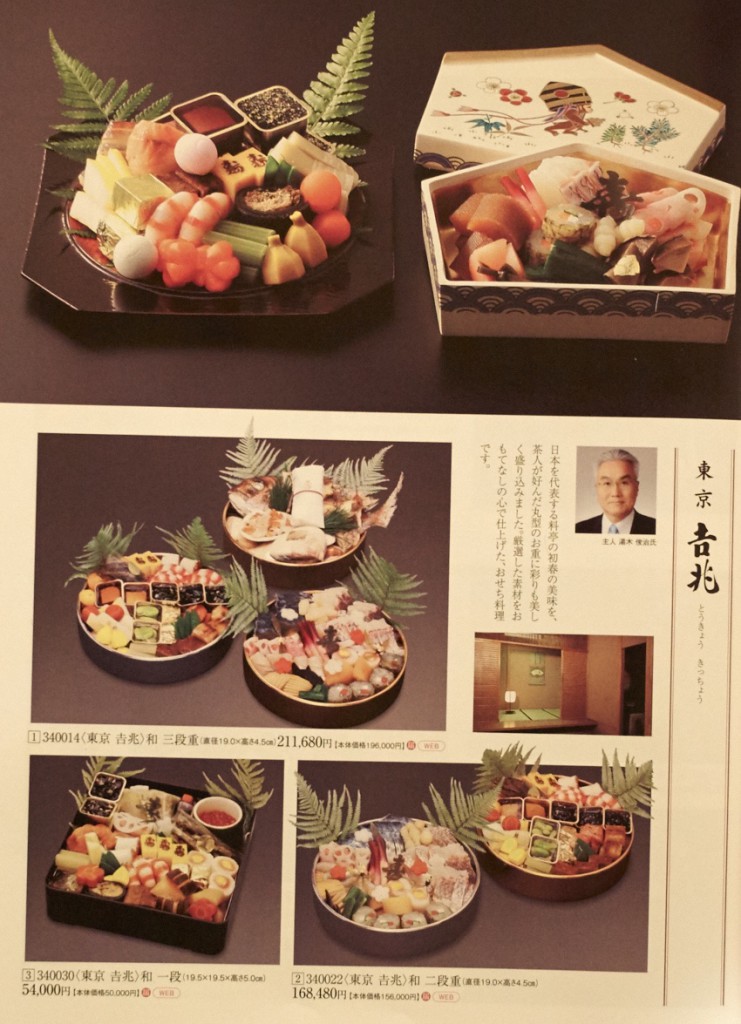

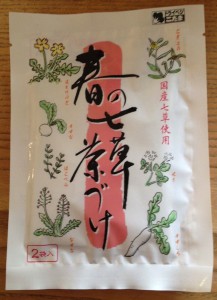

In Japan it is easy to source those herbs both fresh and freeze dried in conveniently packaged containers.

So instead of preparing my family food, which only my youngest daughter would appreciate, I gave it a little twist this year. I combined Nanakusa no Sekku with Sho-Chiku-Bai (pine, bamboo and plum). This threesome – “Three Friends of Winter” is one of the most popular decorative motifs (e.g. the motive on New Year’s chopsticks), representing promise and good fortune.

So I cooked the Japanese rice risotto style: Deglazing the pan with saké and adding the broth little by little while continuously stirring to bring out the creaminess. As a broth I used the liquid from braising bamboo shoots like you would when making Takénoko Gohan. And which were tossed under the rice just before serving. I added pine nuts to the herbs making a raw pesto-like paste to go on top of the rice and added a sprinkle of dried umé boshi powder on top of the dish (hard to see in the picture) to add a splash of color and palate teaser.

This variation of Nanakusa no Sekku was a successful experiment. Even my youngest daughter liked the rice. As she is still waiting for her first tooth to come out, there was not much more for her to try. Here is the recipe that I noted while I was cooking:

For the broth :

– 1.100 ml Dashi

– 100 ml Mirin

– 100 ml light colored soy sauce

– 450g cooked Bamboo

– 2 Turnip

– 2 Mini-Daikon

Put dashi, mirin and soy sauce in a pot on medium heat. Add the thinly cut vegetables, cover with an otoshi buta (or alternatively with a round parchment paper) and allow for low simmering for about five minutes. Remove from the heat and let cool to room temperature. Remove the vegetables from the soup and save for their later use.

For the Pesto*:

– 2 packages of Nanakusa no Sekku-herbs

– 70 g freshly roasted pine nuts

– 100 ml broth

– 15 ml light colored soy sauce

– 1 pinch of salt (optional)

Mix the pine nuts and half of the broth in a blender. Add the rest of the broth bit by bit – depending on your preferred consistency. Proceed similar with the light colored soy sauce, adjusting the degree of saltiness to your liking. Light colored soy sauce is saltier than normal soy sauce, but does not stain the food. So if you substitute regular soy sauce for the light colored soy sauce, beware that it will affect the fresh, green color.

For the rice:

– 275 g Japanese rice

– 100 ml Saké

– 750 ml broth

– 1 El light sesame oil

– 1 Prise Umé boshi powder

Heat the oil in the pot and add the rice, stirring it for one or two minutes until coated with the oil. Deglaze the pot with the saké and add the broth little by little. For a creamy consistency you need to stir constantly, massaging the broth into the rice until it has reached your favorite doneness (mine was al dente).

Before serving mix the cooked vegetables** in the rice and arrange it nicely on a plate. Top with the pesto and sprinkle some umé boshi powder over the dish .

We enjoyed our Sho-Chiku-Bai Nanakusa no Sekku with a glass of chilled Junmai Kimoto Saké from the Daishichi brewery, which I will be introducing in more detail in a separate post.

___________

* The amount of pesto that I got was good for six people, whereas the rice was for two adults, two little girls and a baby only. Next time I will cut the recipe in half.

** I used way too much bamboo for the dish. The bamboo flavored the broth nicely, but was too much to mix with the rice that I cooked. I assume that 150 g bamboo would probably have been more than enough.