For some reason packing seems to be faster than unpacking. By now it has been a few weeks since we came to Berlin, but the most prominent decoration of our home remain to be towers of boxes, waiting in each corner to be unpacked, reminding me every day that there is still quite some work ahead of me.

We like Japan too much for any euphoric feeling to ever occur about us moving back to Berlin, but at the same time there is some excitement in starting all over, that keeps you going – until that one day when you wake up with a ‘hangover’. Actually you carry that feeling around for quite a bit, but then one day you wake up realizing that you are in the middle of a reverse-culture-shock. At least the adults in our house, for whom life in Berlin is something familiar. Our girls however are struggling a bit more. They are German, look like Germans and speak German, but were raised in Japan. Now they need to find their way in a world where no one understands that to them everything is new and strange. Despite the fact that Berlin is tiny compared to Tokyo, life is somehow faster, is duller, is tougher. More elbows, less service, more egoism, less honesty, more swearing, less respect, more dirt, less kindness…

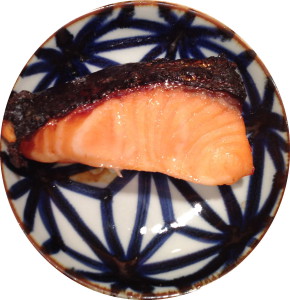

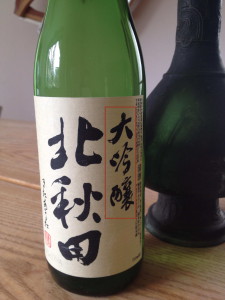

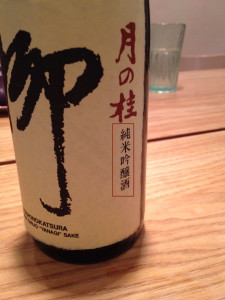

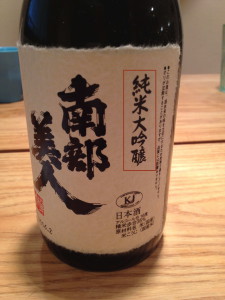

Even though it has been quite on “The Taste of Japan” lately, even though I was busy finding a new home, a new school, new kindergarden and nursery while unpacking and sorting hundreds of boxes to get this family back to a state of normality, it was not quite in my kitchen. Behind the scenes I captured every kitchen on the way and worked on pickling Ume Boshi (pickled plums) and pickled apricots. I also made Yukari (dried and pulverized red Shiso leaves from the plum pickling) and Ume Su (plum vinegar), documented the making of rice and sushi-rice, took my nuka-pot (pot for rice bran fermentation) on a journey around the word and further developed my love for sake where I will be able to share some exciting news soon. I am excited about this restart to cover culinary Japan for you.

And to answer the question if we have arrived. Generally speaking – yes we have. We will also feel at home once we have replaced the boxes by pictures to decorate our walls. But we also know that there will always be some sort of yearning to go back to the land of the rising sun, no matter where life will take us.