Nothing goes to waste in the Japanese Kitchen. Nothing. I have internalized this appreciation that I have learned from Andoh sensei years ago in our very first encounter. After a while it becomes not only a daily practice and routine, it also becomes kind of a hobby to find out how much (more) you can (re)use from an ingredient.

I usually consume white rice. It cooks and behaves widely different than brown rice – and – admittedly because I like it better. Though I do make sure to get my nutrients back in eating nuka zuké (Japanese vegetables pickled in rice bran) and adding different grains to my rice. Which leads me directly to using food – in this case rice – fully. Nuka (rice bran) is a byproduct when milling rice. It is being used as a pickle medium for vegetables and also in the cooking liquid (nuka-jiru) for e.g. fresh bamboo shoots to neutralize the natural occurring toxic and bitter components.

Some of the nuka remains on the rice and this is why you should wash your rice thoroughly before cooking or it will not cook as well. Coming back to my favorite Japanese kitchen mantra ‘Nothing is going to waste in the Japanese kitchen’: Save that water (togi-jiru) and dedicate it to a useful purpose. Need ideas? Here are my top five ways to reuse the water from washing rice

Cooking: The rice oils and the starch in togi-jiru neutralize bitter enzymes that allow the sugars in the vegetable to be more noticeable. Use togi-jiru instead of water to cook e.g. daikon, sweet corn or burdock for a palate-pleasing sweetness.

Cooking: The rice oils and the starch in togi-jiru neutralize bitter enzymes that allow the sugars in the vegetable to be more noticeable. Use togi-jiru instead of water to cook e.g. daikon, sweet corn or burdock for a palate-pleasing sweetness.

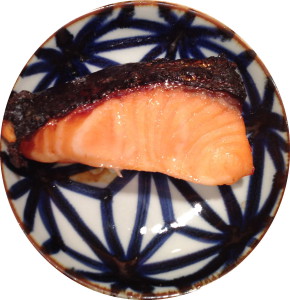

Beauty: Carefully pour off the water after the sediment has formed on the bottom. Feel it. It is soft and silky. A wonderful cream. I use it for my hands, as it doesn’t leave a greasy film behind and it doesn’t have artificial ingredients that I wouldn’t want to get on my food. Even better: it removes unwanted odors like fish or garlic.

Beauty: Carefully pour off the water after the sediment has formed on the bottom. Feel it. It is soft and silky. A wonderful cream. I use it for my hands, as it doesn’t leave a greasy film behind and it doesn’t have artificial ingredients that I wouldn’t want to get on my food. Even better: it removes unwanted odors like fish or garlic.

Plants: Frugal cooks also save the second and third wash to water their plants. The containing nutrients really perk them up.

Plants: Frugal cooks also save the second and third wash to water their plants. The containing nutrients really perk them up.

Kitchen Hygiene: Togi-jiru is effective in removing odors from your pots and pans (e.g. after cooking fish). It can also be used in cleaning the tiny contours and crevices of earthenware pots, rice bowls and teacups.

Cleaning: So far I have always used my togi-jiru up for cooking, as a cream or for my pots and pans. But apparently it is said to be also great for giving a nice shine to your floors, shower, bathtub, or toilet. So if you happen to have any left over togi-jiru put it in a spray bottle when wiping down your house.

Cleaning: So far I have always used my togi-jiru up for cooking, as a cream or for my pots and pans. But apparently it is said to be also great for giving a nice shine to your floors, shower, bathtub, or toilet. So if you happen to have any left over togi-jiru put it in a spray bottle when wiping down your house.

You can keep togi-jiru for up to five days in the fridge an. This way you can collect the water from washing your rice for several days. The sediment at the bottom of your jar will thicken with each addition, when you pour off the water above it to make room for the new washing water.